Our Inspiring Capitol Dome

by Ken Rock, MSDC Editor

I recently had the good fortune to visit Capitol Reef National Park in south-central Utah. The park was named, in part, after the Capitol Dome in Washington, DC because of a feature in the Navajo Sandstone that reminded early explorers of the U.S. Capitol building in the nation's capital. Does the photo below conjure up the same image to you?

Curiously, the second part of the park's name, reef, refers to any rocky barrier to land travel, just as ocean reefs are barriers to sea travel. This connection to the folded and eroded rock formations in the park is easier to make, at least for me!

The park is ~60 miles long on its north-south axis and averages just 6 miles wide. The main geologic feature of the park is the Waterpocket Fold, a rocky spine that extends the entire length of the desert landscape of the park. Although Capitol Reef may be Utah's least known national park, it is certainly one of the best! The park is filled with brightly colored sandstone cliffs, beautiful white domes, and contrasting layers of sedimentary rocks.

Capitol Reef National Park's geologic story reveals a nearly complete set of Mesozoic-era sedimentary layers. For 200 million years, rock layers formed at or near sea level. About 75 to 35 million years ago, tectonic forces uplifted them, forming the Waterpocket Fold. Forces of erosion have been sculpting this spectacular landscape ever since.

The Waterpocket Fold defines Capitol Reef National Park. A nearly 100-mile long warp in the Earth's crust, the Waterpocket Fold is a classic monocline, a "step-up" in the rock layers. It formed when a major mountain building event in western North America, the Laramide Orogeny, reactivated an ancient buried fault in this region. Movement along the fault caused the west side to shift upwards relative to the east side. The overlying sedimentary layers were draped above the fault and formed a monocline – the longest exposed monocline in North America at nearly 90 miles in length. The rock layers on the west side of the fold have been lifted more than 7,000 feet higher than the layers on the east.

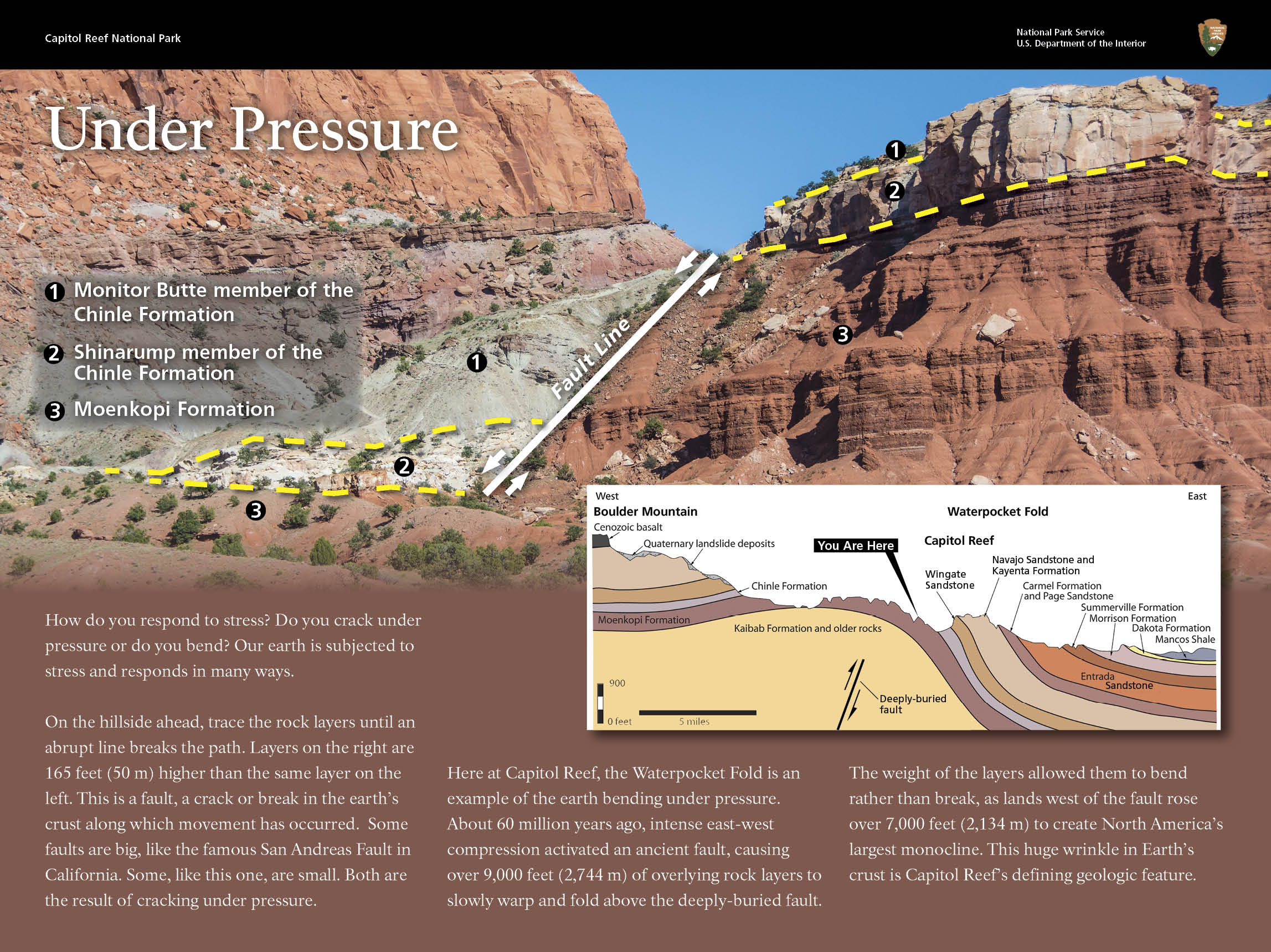

It is interesting to note that although a small fault is shown in the image below, the more than 9,000 feet of rock layers overlying an old and deeply buried fault usually did not break from motion along the fault. In fact, these rock layers slowly warped and folded in an "S" shape as they rose more than 7,000 feet in elevation to create what is now the Waterpocket Fold. Erosion has exposed 19 different rock formations in the park, as shown in the inset drawing below, spanning a 280-million-year timeframe in the earth’s 4.6-billion-year history.

More recent uplift of the entire Colorado Plateau and the resulting erosion has exposed this fold at the surface within the last 15 to 20 million years. A quick review of a map of the national park reveals that the fold forms a north-to-south barrier that has barely been breached by roads. When viewed from the east, it is easy to see why early settlers referred to the parallel impassable ridges as "reefs," from which the park got the second half of its name.

Capitol Reef National Park is filled with canyons, cliffs, towers, domes, and arches. The Fremont River has cut canyons through parts of the Waterpocket Fold, but most of the park is arid desert. A scenic drive shows park visitors some highlights, but it runs only a few miles from the main highway. Hundreds of miles of trails and unpaved roads lead into the equally scenic backcountry.

The ongoing erosion of the rock layers has created the stunning scenery in the park and serves as a reminder that, as author and historian Wallace Stegner has said, "Geology knows no such word as forever."