Michigan Copper

Presentation by Jim Hird

Synopsis by Andy Thompson, MSDC Secretary

The purpose of this synopsis is to provide our readers with the flavor of our presenter’s program and to encourage everyone to visit the full-length video recording available through our club’s website: mineralogicalsocietyofDC.org. It is not intended as a transcript or verbatim record of the event.

MSDC’s June program presenter, Jim Hird, brought a lifetime of professional mining expertise as well as decades of specimen collecting experiences which he shared with his enthusiastic listeners. Jim, a self-described rock hound, took his undergraduate training at Houghton Technical Institute located on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula (UP). His professional career focused primarily on coal mining in West Virginia. But it was his decades of studying the copper mines of Michigan’s UP, serving as a mineral club president, and leading countless field-collecting trips that provided the grist for his telling the fascinating story of the Keweenaw mines.

The name “Keweenaw” refers both to the northernmost part of Michigan’s U P as well as to the county in which most of the state’s copper mines were located. The short title for his presentation, Jim said, “Michigan Copper,” could be more accurately named “The Keweenaw: Its Mines and Minerals, Then and Now.”

Early Geological History of the Region

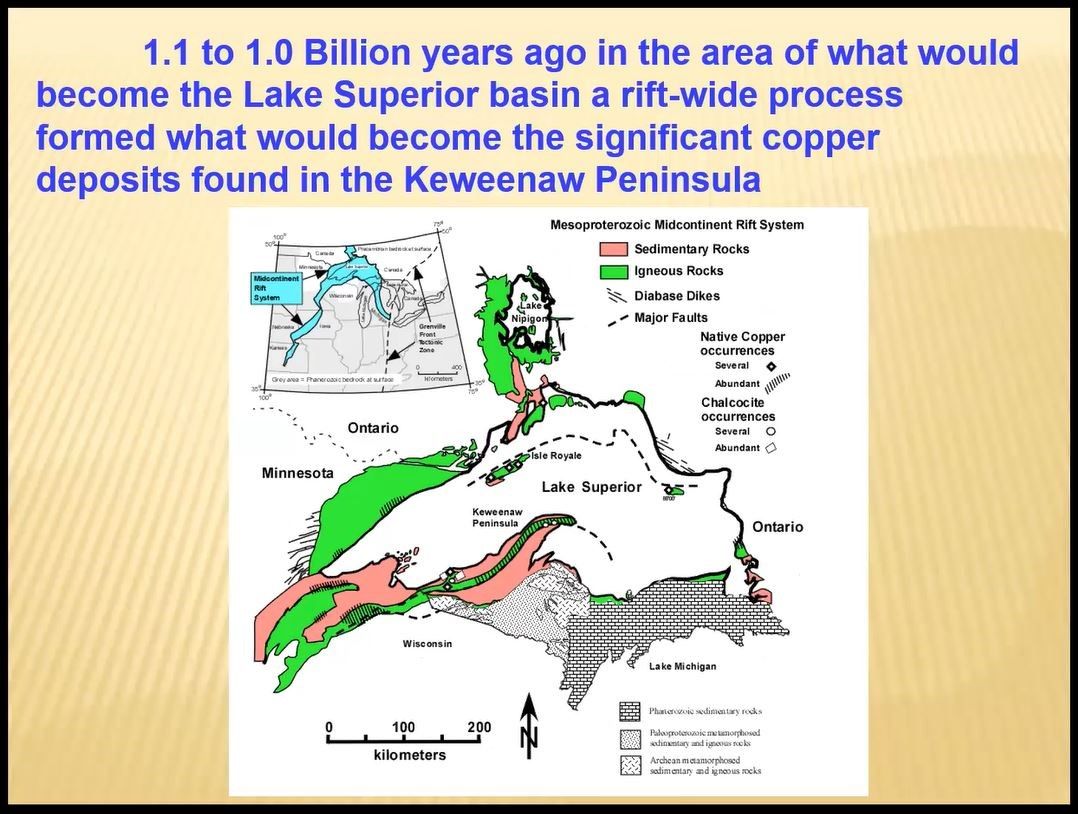

Jim began his presentation by taking his audience on a trip back in time to the geological origins of the upper-most area of Lake Superior basin when a rift, highlighted in the blue region of the insert pictured below, opened up. Simply put, over millennia, the region filled in with copper deposits.

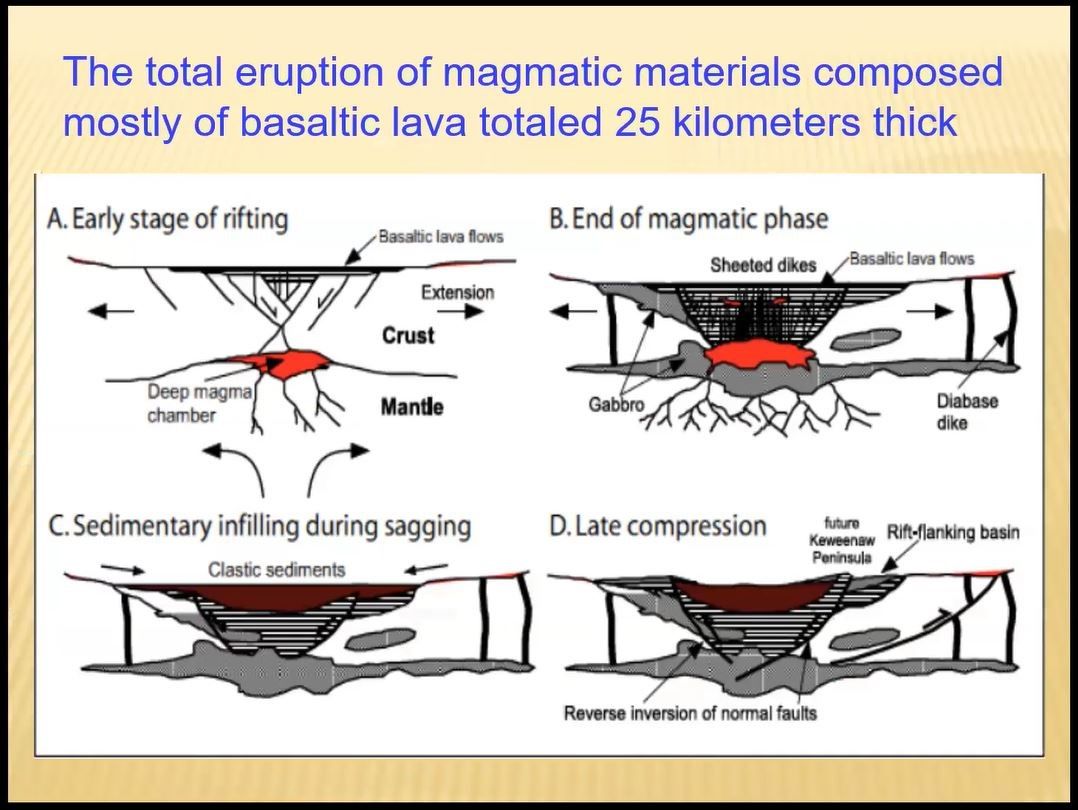

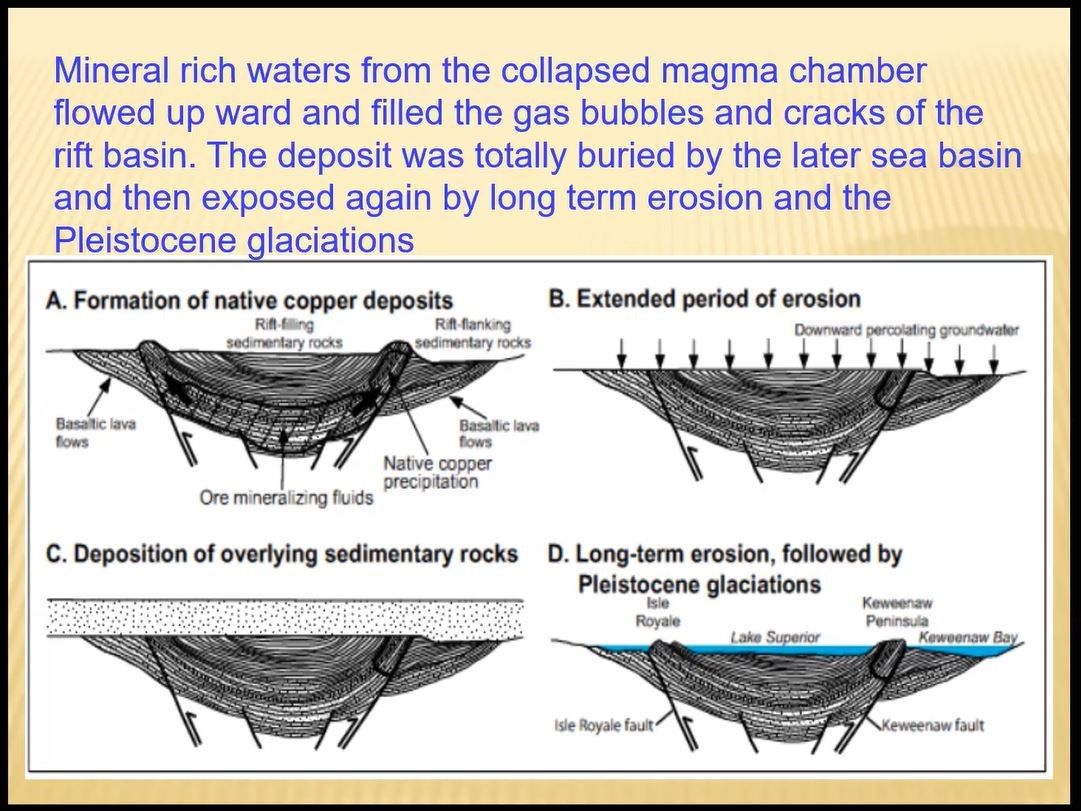

The following slide portrays the four stages of how the rift opened (A), and subsequently filled in with alternating layers of magma (B), gravel and sand accumulated above the magma chamber (C), and then compressing into a large swath of land which later became the Keweenaw Peninsula. Some of the land extended north under today’s Lake Superior waters and reemerged to become the Isle Royale.

That deposition process took millions of years and the concave shaped alternating layers of mud and magma, traces of which are still evident in the shape of the copper seams discovered by miners of the 19th and 20th centuries.

The following slide illustrates the multistage processes by which the solidified bubbles and spaces in the rising magma became the recipients of the mineral rich rising waters. As noted, those bubble and cracks became the home to later-arriving extensive deposits of copper metals. Jim noted those mineral rich waters contained not diluted traces of copper, but pure “native copper,” which made this UP rift basin somewhat unique in the world.

Early Copper Mining and the Nation’s First “Gold” Rush

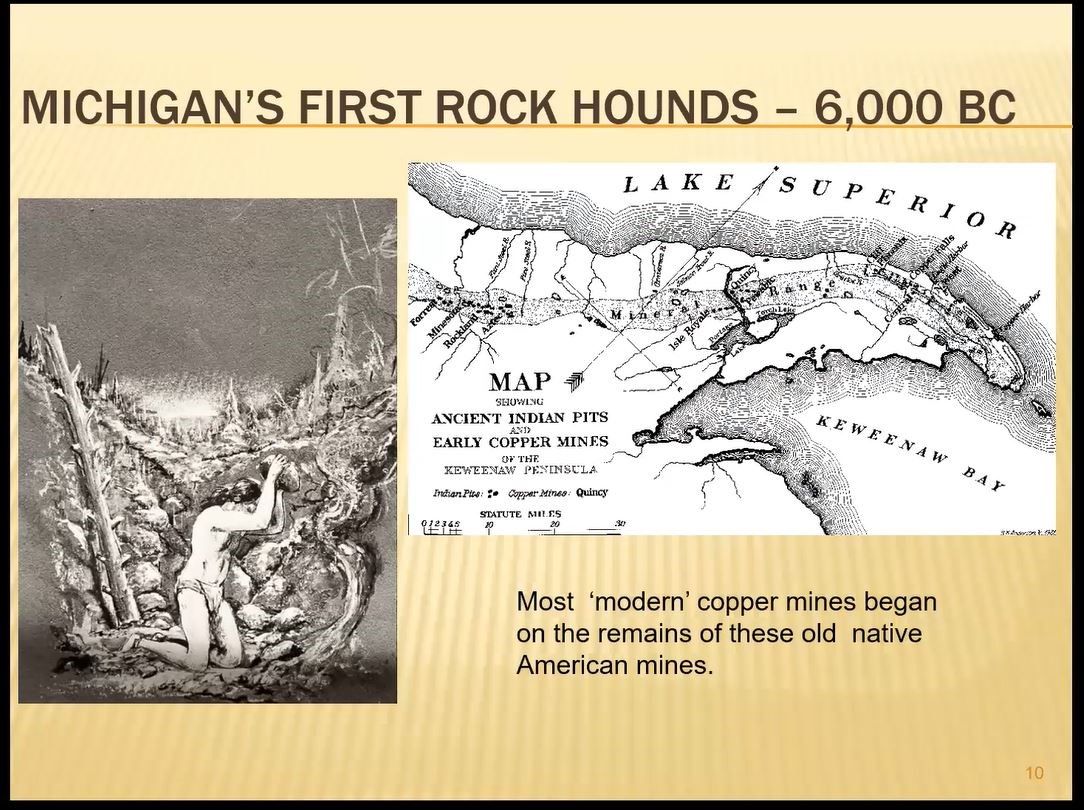

“The native Americans of this region,’ Jim said, ‘dating back more than six thousand years ago, undoubtedly would have found the shiny copper mineral pieces sitting along the stream banks and ground, available without any digging.” He showed examples of the early native Americans’ early copper tools which they used as instruments for cutting, making fish hooks, and spear tips.

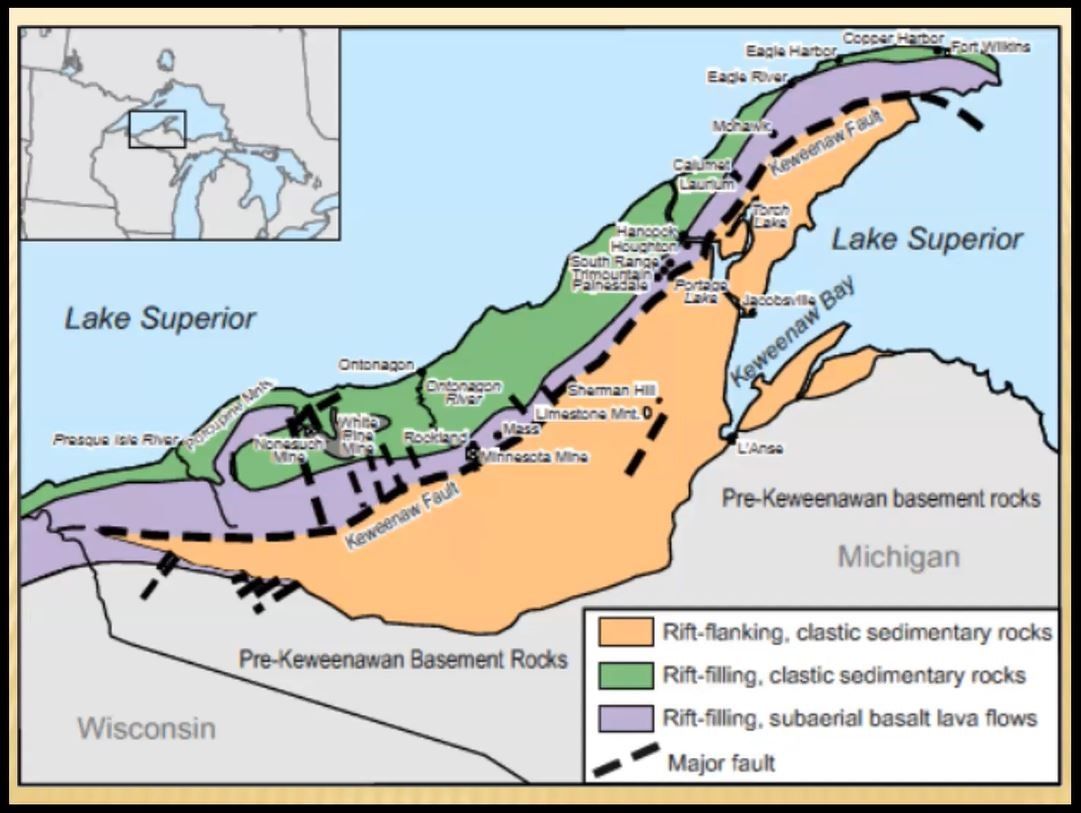

The dotted black line in the illustration below shows the location of the Keweenaw fault line which runs along the middle of the UP. It is along that line, Jim said, where historically the copper mines have been located, between the clastic sedimentary deposits on the south flank, and the subaerial basalt lava flow depositions to the north.

Jim told the wonderful story of how Benjamin Franklin, in 1783, who had some knowledge of the copper mines of the UP and Isle Royale, negotiated the terms of the Treaty of Paris so they drew the America’s new northern boundary line so the UP and Isle Royale was clearly an undisputed possession of the American colonies, and not of the British empire. Jim referred to the excerpt, reprinted below, from Angus Murdoch’s Boom Copper: The Story of the First U.S. Mining Boom (2012), which recounts Franklin’s diplomatic triumph.

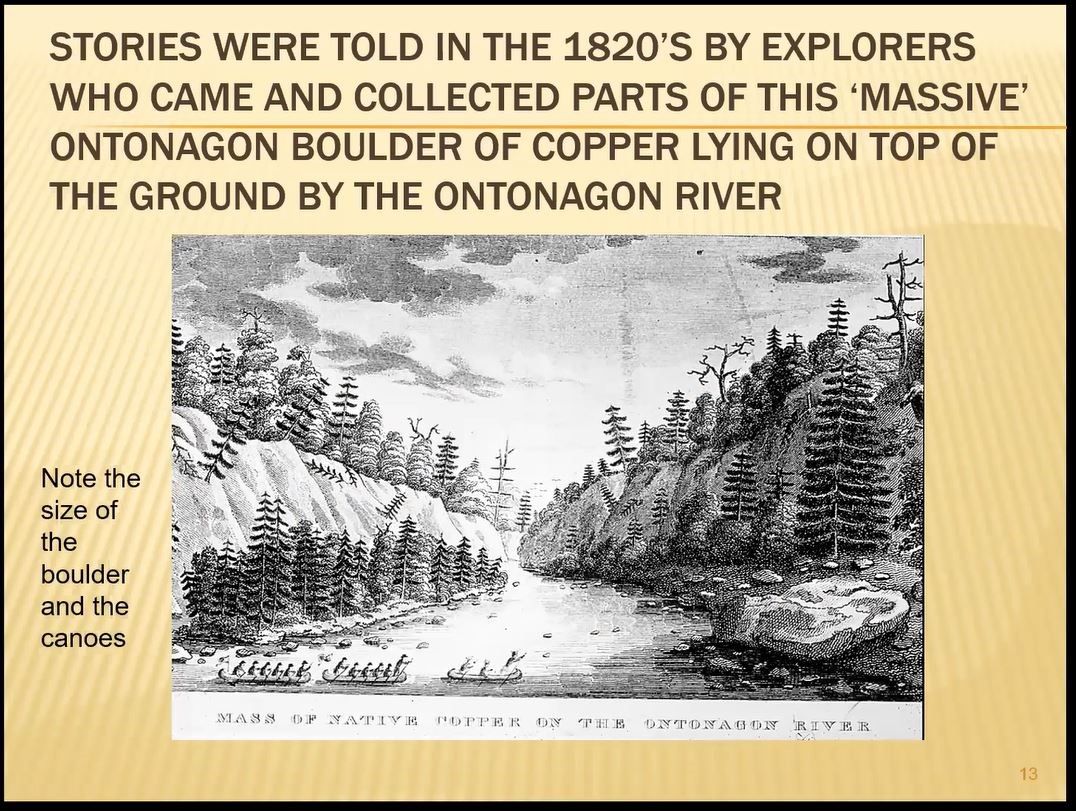

The illustration and photo below provide evidence of the copious copper deposits found in the area, specifically the boulder shown on the lower right of the drawing, on edge of the Ontonagan River.

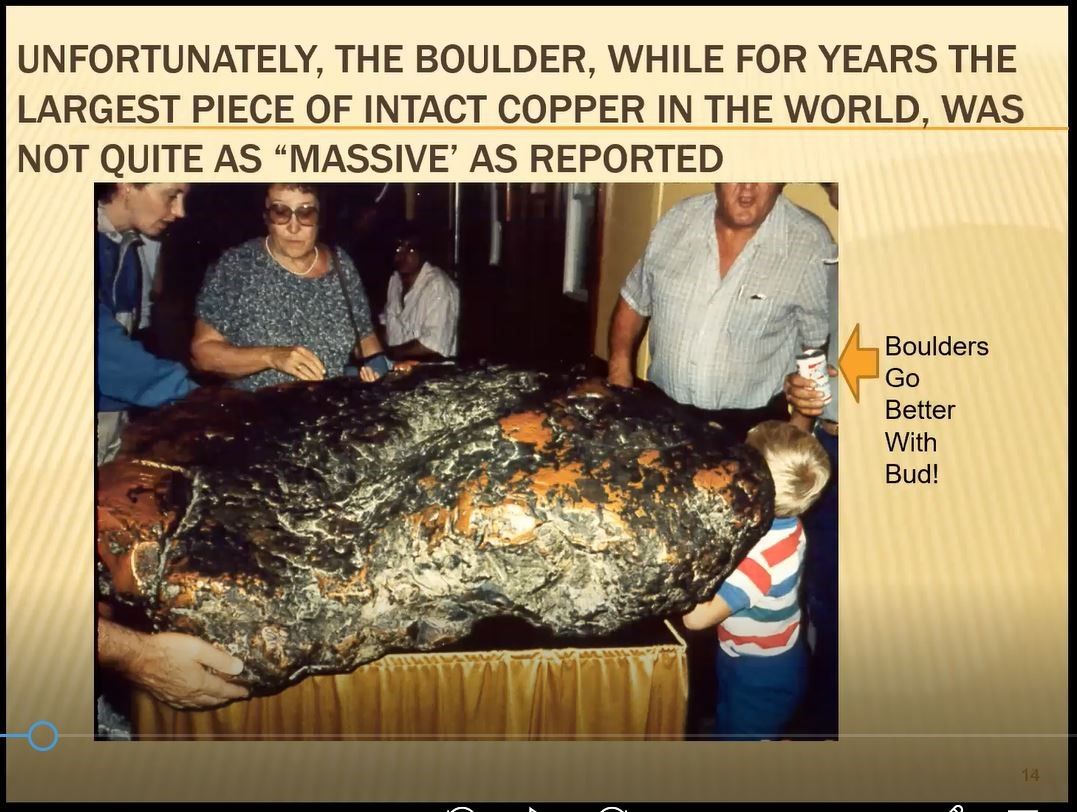

The actual massive boulder of pure copper shown above has been in the possession of and on display in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. Notice in the photo below the arrow pointing to the adage: “Boulders go better with Bud.”

The history of copper mining in the U.S. took a giant step forward when, in 1840, the State of Michigan commissioned Douglas Houghton to survey the region. As a result of his report, Jim said, the nation’s first mineral rush was on -- even before the more famous “gold rush” of the (18)49ers. It was in honor of that same Mr. Houghton that Jim’s undergraduate institution was initially named, Houghton College.

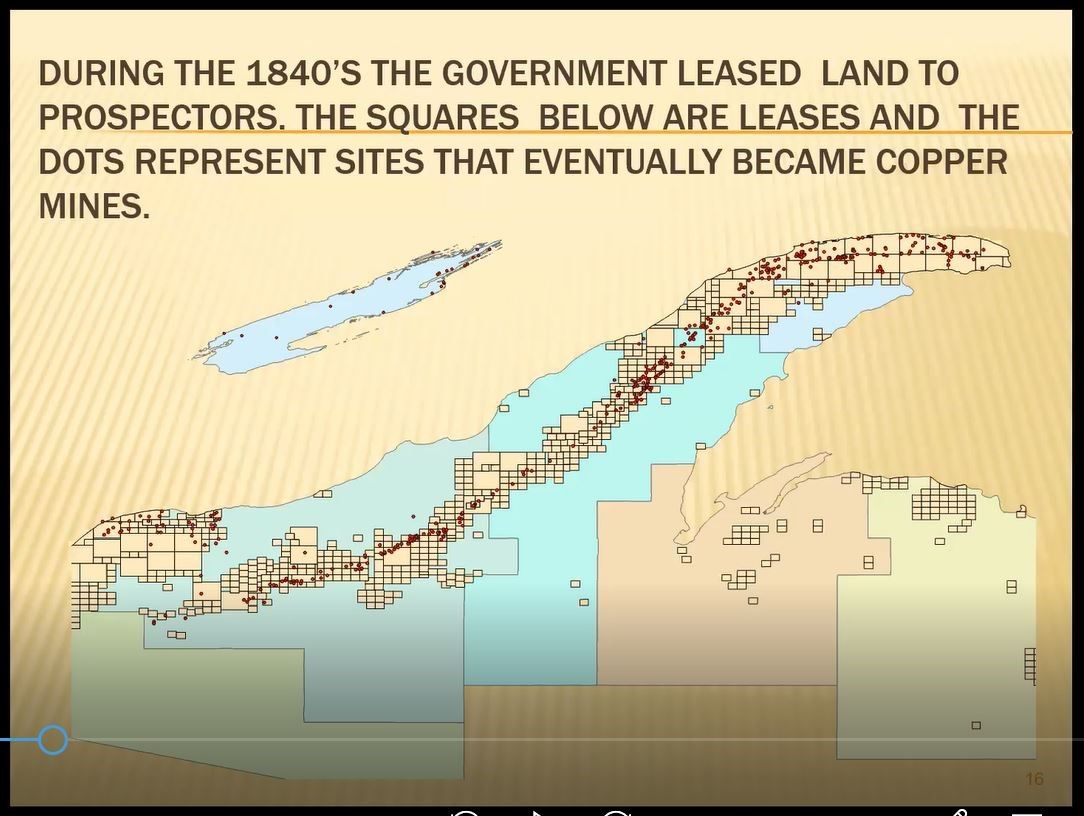

Jim included the following slide, which, he pointed out, illustrated the nature of that famous 1840s copper rush, namely an exploration into the unknown. The slide below contains many empty squares which marked the areas for which hopeful miners applied for and were given leases to mine. The far fewer red dots represent the areas were copper was actually found. He commented that the abundance of squares having no dot, is clear evidence “the majority of the early miners and lease holders had no idea of where the copper deposits were to be found. They were guessing.”

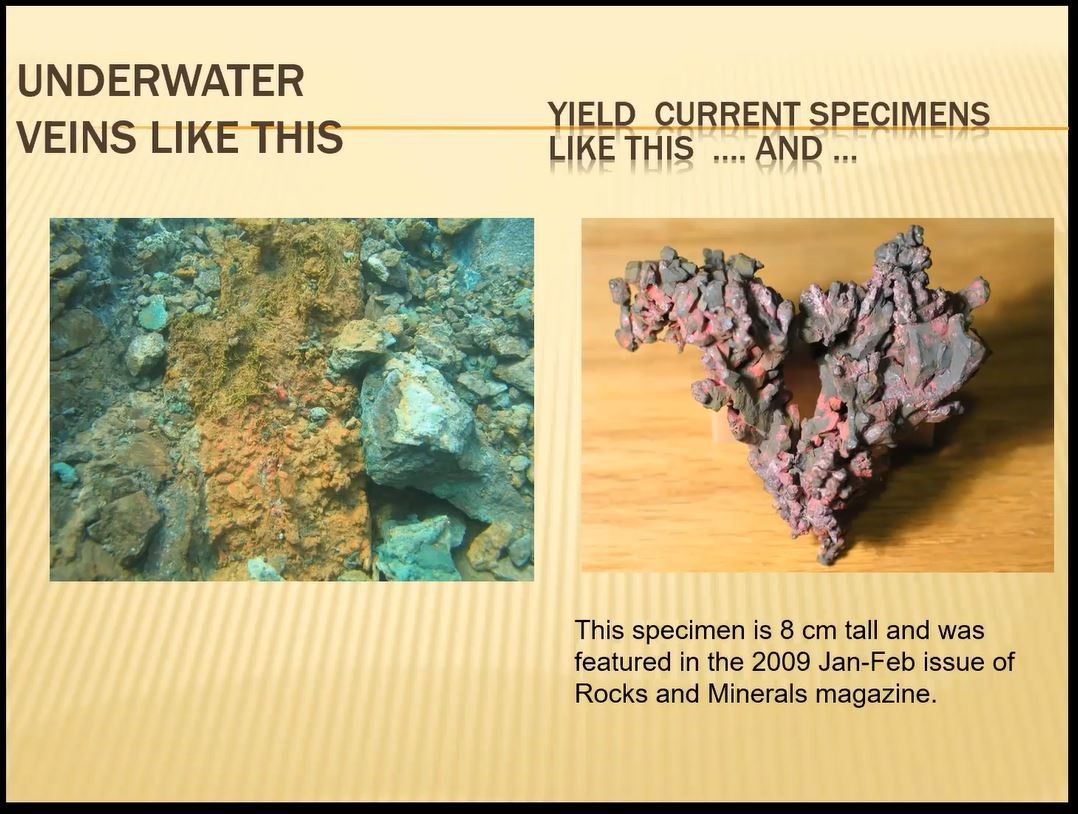

Even to this day, as shown below, mineral hunters occasionally find sizable veins and chunks of copper submerged in the waters of Lake Superior.

Interesting Copper Mines of the Upper Peninsula

A significant part of Jim’s presentation to MSDC included specific information about the many mines along the fault line of the UP. Readers will recall that Jim’s longer title for his presentation was “The Keweenaw: Its Mines and Minerals, Then and Now.” The fruit of his extensive knowledge of the mines became evident as he showed “then and now” photos of many of those individual copper mines.

The long-closed Cliff Mine, for example, has left behind tailing dump sites which, as shown in the four photos below, still yield up copper and related treasures for sharp eyed collectors.

Another fascinating fact about the Keweenaw mines is that many contained very large slabs of native copper, which, in the late 19th century, due to the mining sites being relatively inaccessible to roads and large equipment, could not be lifted, readily excavated or transported. Instead, Jim explained, the miners had to use hand-held tolls to painstakingly carve the slabs into smaller pieces suitable for transportation. Careful examination of the photo below will reveal a typical copper crew working above ground, and a few long pics and large hammers used by pairs of men “double jacking” to laboriously cut the slab into smaller pieces.

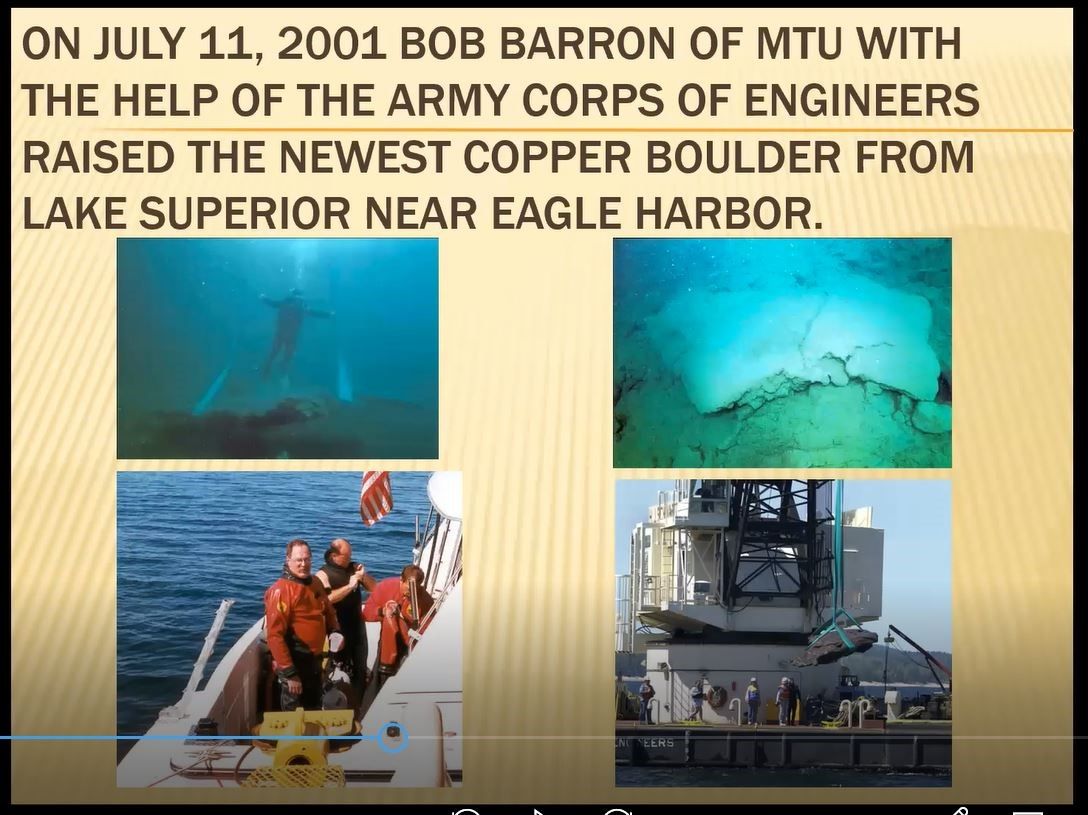

Twenty years ago, as shown below, one mineral hunter discovered a native copper boulder beneath Lake Superior. It was so large, he recruiting the Army Corps of Engineers to haul it from Lake Superior and deliver it to a state museum for display.

Unusual Minerals Associated with Specific Copper Mines

Jim treated his audience to photos showing interesting aspects of many of the copper mines in the UP, including the Mohawk, C & H, Wolverine, Seneca, Quincy and Caledonia mines. Each of these, and many others, had unusual minerals or unique features that were worthy of comment.

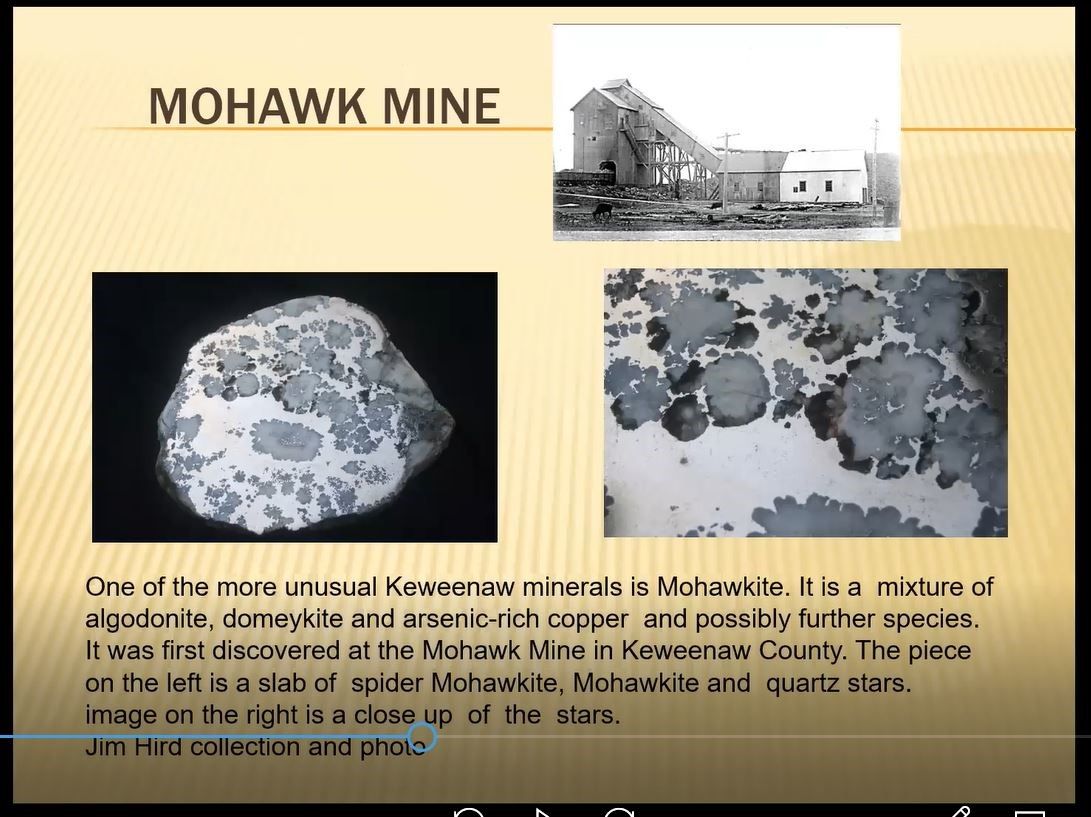

The Mohawk Mine below, for example, contains a photo of a specimen of Mohawkite, along with a close-up shot, which is composed of a mixture of algodonite and domeykite minerals, both of which are forms of arsenic-rich copper.

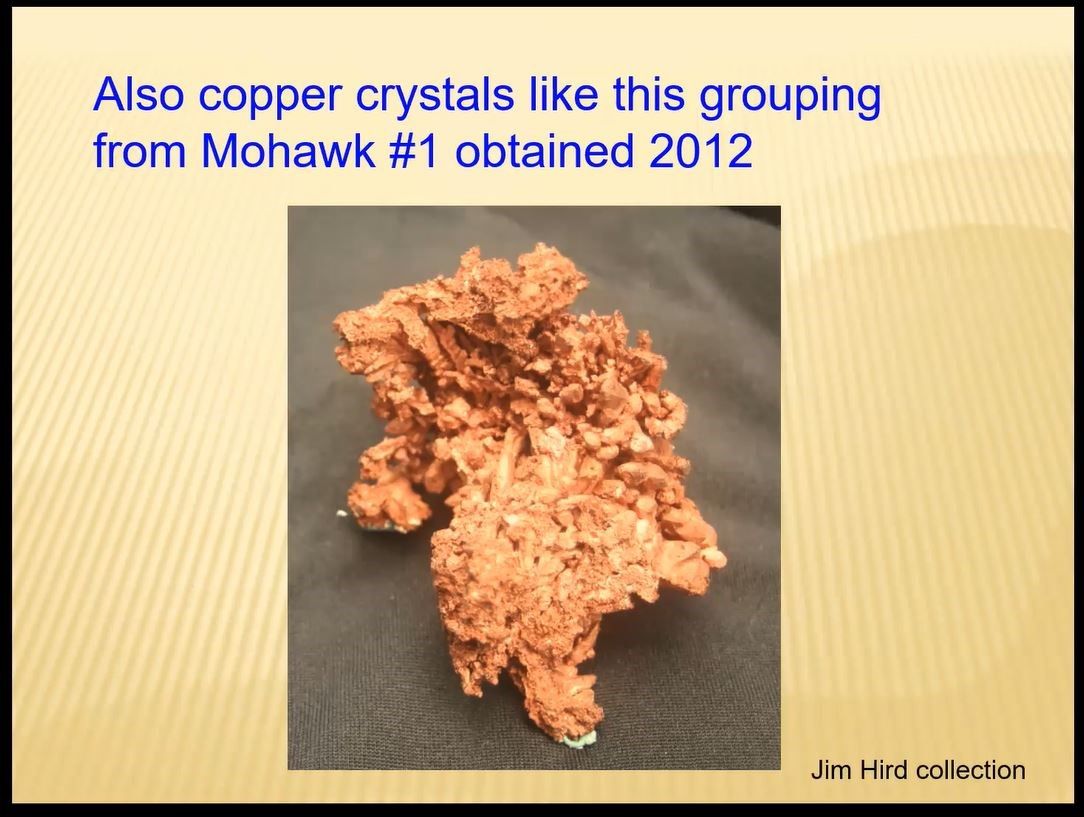

The Mohawk mine, of course, also has numerous classical forms of copper crystals, one of which, below, Jim collected in 2012.

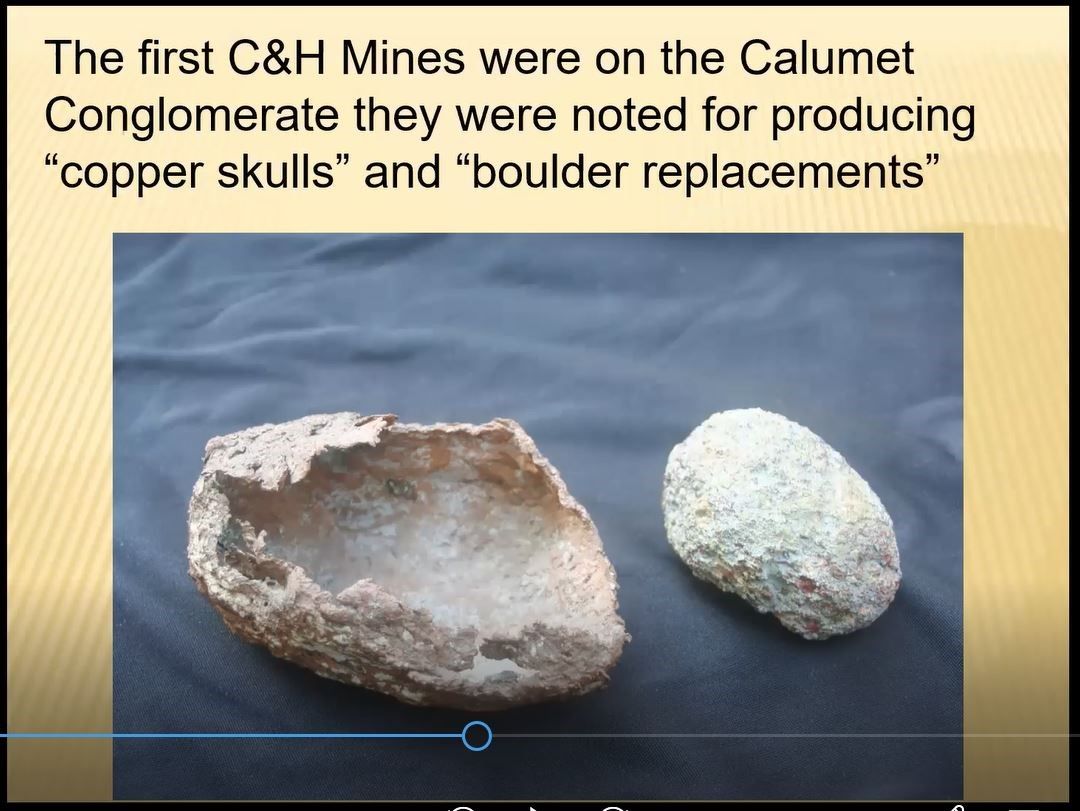

Just as the term “Keweenaw” signifies the northern-most county of the Upper Peninsula, so too the term Calumet represents the county immediately to the south of Keweenaw County. But Calumet also was the name of a village and of a mine. One of its unique features was a form of copper casing named “copper skulls” shown below. The smaller egg-shaped mineral next to the skull was found originally within the skull and its slight blue-tint is a composite of copper chloride.

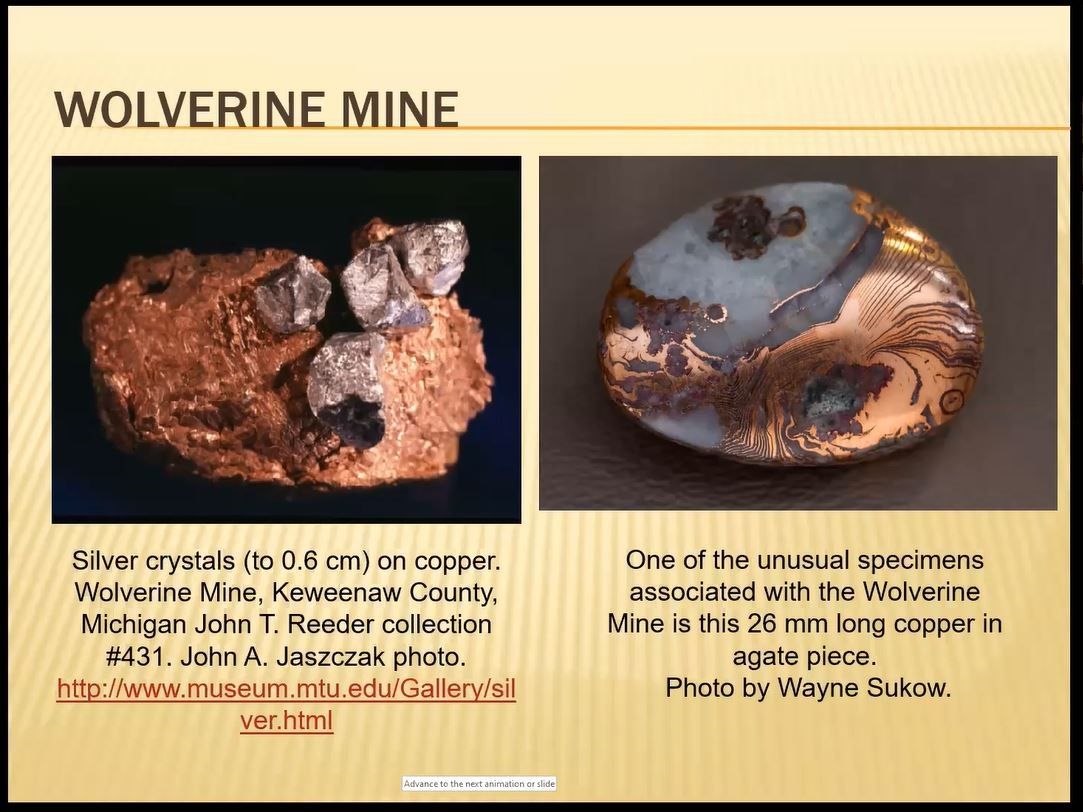

Jim and fellow collectors have also found special specimens at the Wolverine mine, two of which are shown below. Given their shape, they illustrate their origin was a tiny magmatic bubble, into which copper-rich water flowed and crystalized. The first copper specimen to the left is topped with a few silver crystals. The second, a polished specimen, photographed by Wayne Sukow, includes alternating agate and copper bands. Jim noted the latter are highly treasured by UP collectors.

The multiplicity of copper mines in the UP is matched by the many variations of copper minerals found within them. As noted in the above photo, so long as a determined and enthusiastic collector has a metal detector in hand, the copper mineral specimens can be found even in commonplace areas such as rock-filled parking lots.

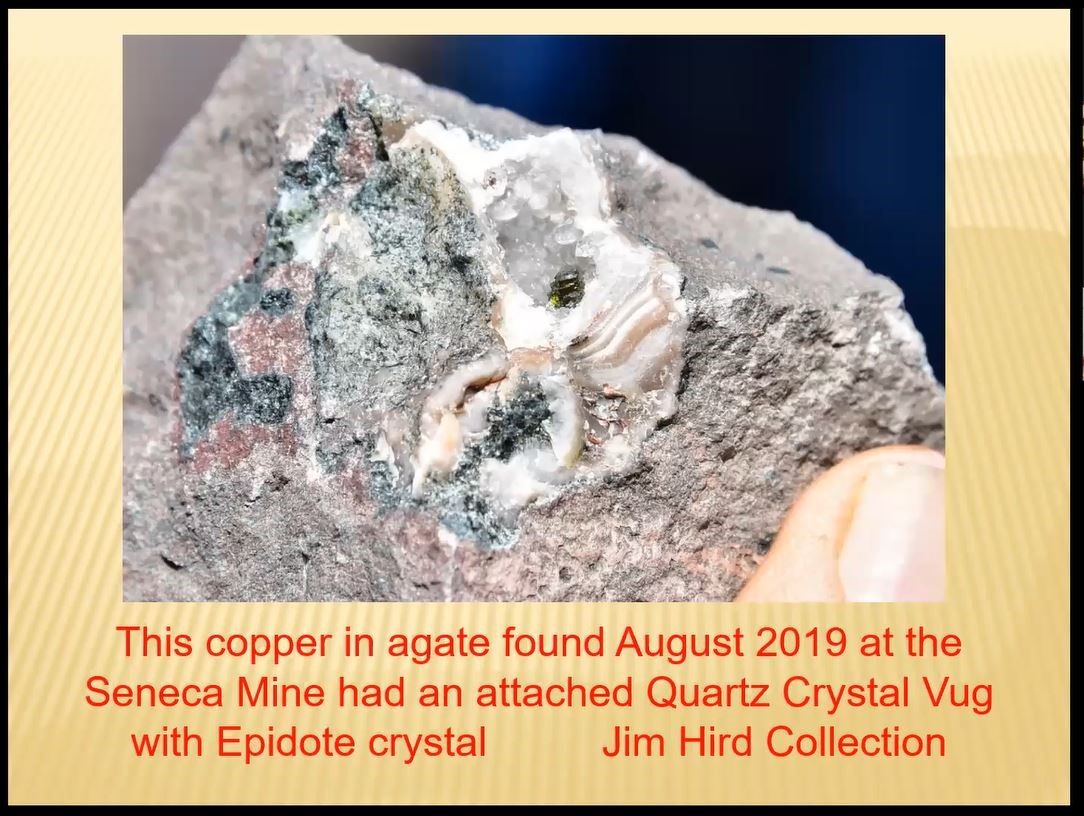

Another unusual specimen Jim found in 2019, came from the area of the Seneca mine and, shown below, it is a copper within agate, with an attached quartz vug containing an epidote crystal.

Another mine worth visiting, especially as a walking tour, is the Quincy mine which shuttered its operation in 1970. As shown in the three photos below, the 9,000-foot depth of the Quincy #2 mine, required a very large hoist system. The steam-powered hoist used at the Quincy mine was the largest in the world. The large ball-like feature, the grey colored drum shown below, contained the hoist cable, and is 35 feet in diameter.

The very tall shaft house Jim portrayed in the introductory and first slide of his series, is shown at the beginning of this synopsis, and illustrates the “then and now” of the mine’s history and current tourist repurposing. The blue colored shaft building on the left is what it looks like “now,” while the rusty grey building was what it looked like back “then.”

The Caledonia mine is built into the side of a mountain and successfully operated until the 1870s, and then again very briefly in the 1950s. Today it welcomes visitors and provides mineral education and abundant opportunities for collectors to work the piles to find copper, silver, quartz, feldspar calcite and epidote. Jim showed photos of three red and one light brown datolite specimens showed below. He loves the rich colors of datolite and it is one of his most favorite minerals to collect. Datolite is a calcium boron silicate hydroxide mineral that occurs in fine grained nodules and are commonly found in old copper mine dumps.

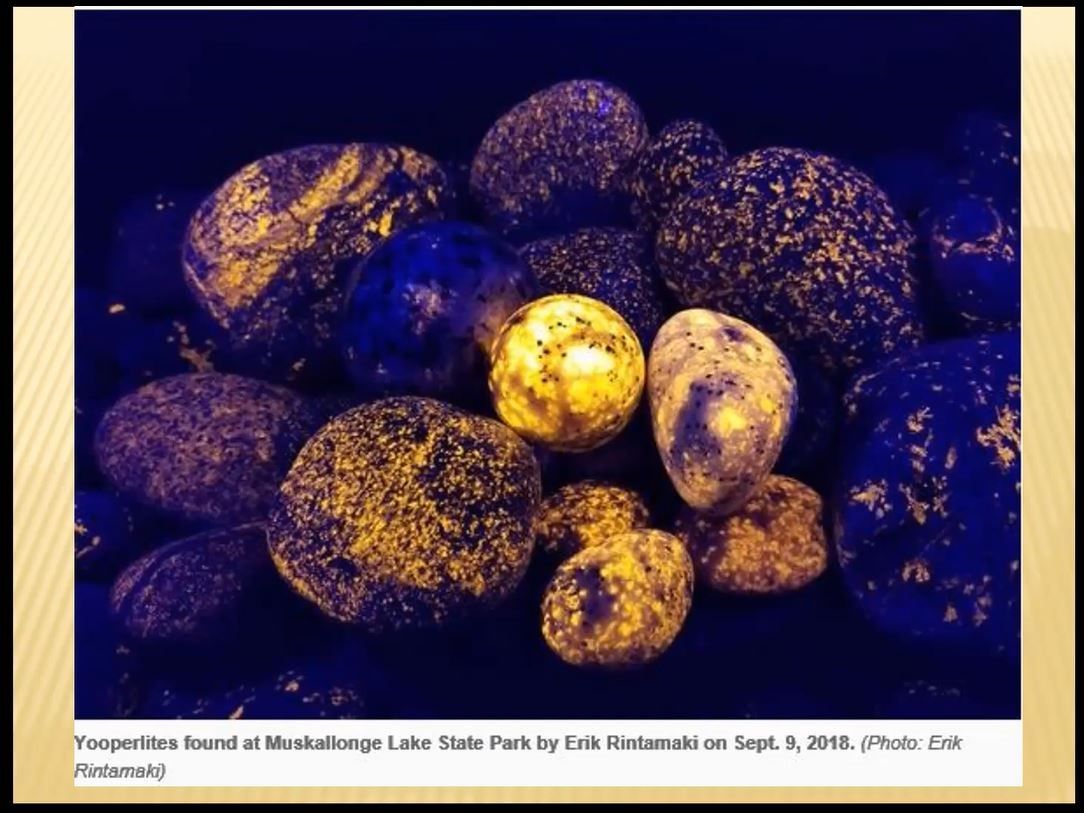

Sometimes, collectible minerals can still be found right out in the open, as long as, Jim said, you carry with you a black light and you are willing to wait until after sunset to find fluorescent rocks. Some collectors call them “Yooperlites,” named informally in honor of inhabitants of the Upper Peninsula. The rocks are water-rounded and rich in fluorescent sodalite, just sitting on the lake beach waiting for nighttime collectors to take them home. Jim has collected there, with some success, he said, as recently as 2020.

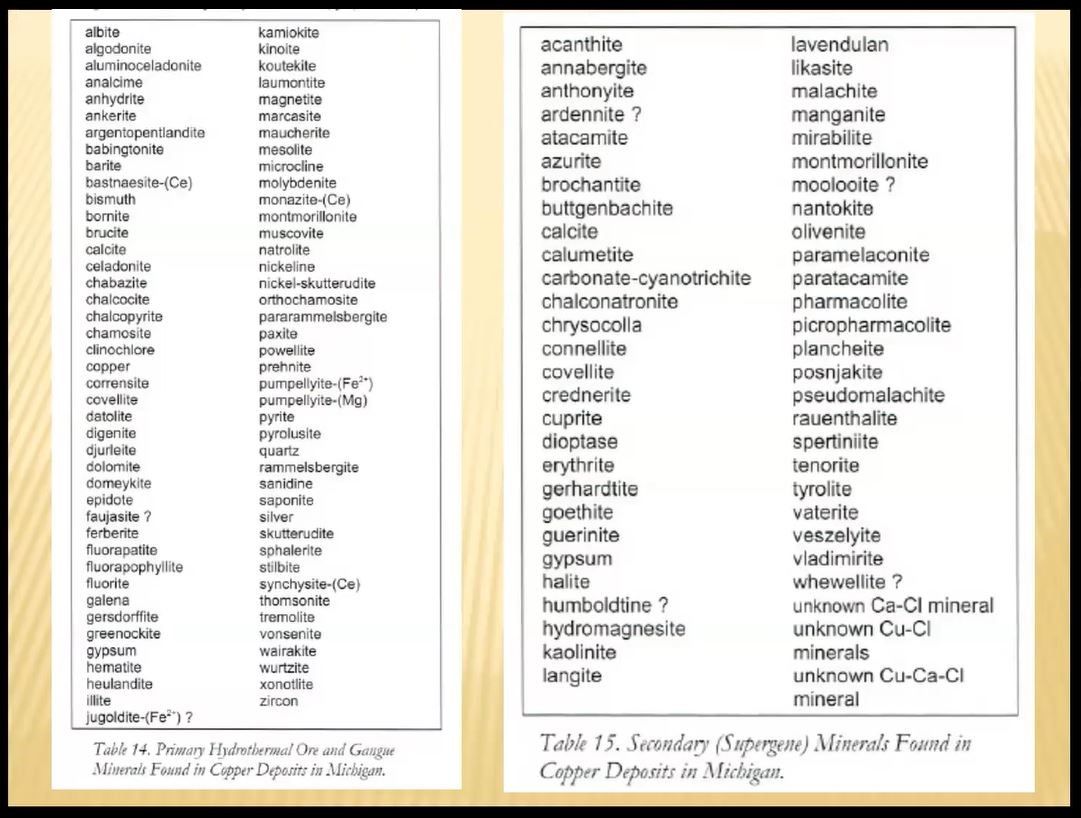

Collectively, the range of copper minerals found throughout the UP mining areas is extensive and includes those identified below in the two lists, of primary and secondary copper minerals. Jim said: “I don’t have all of them yet, but my collection is well on its way.”

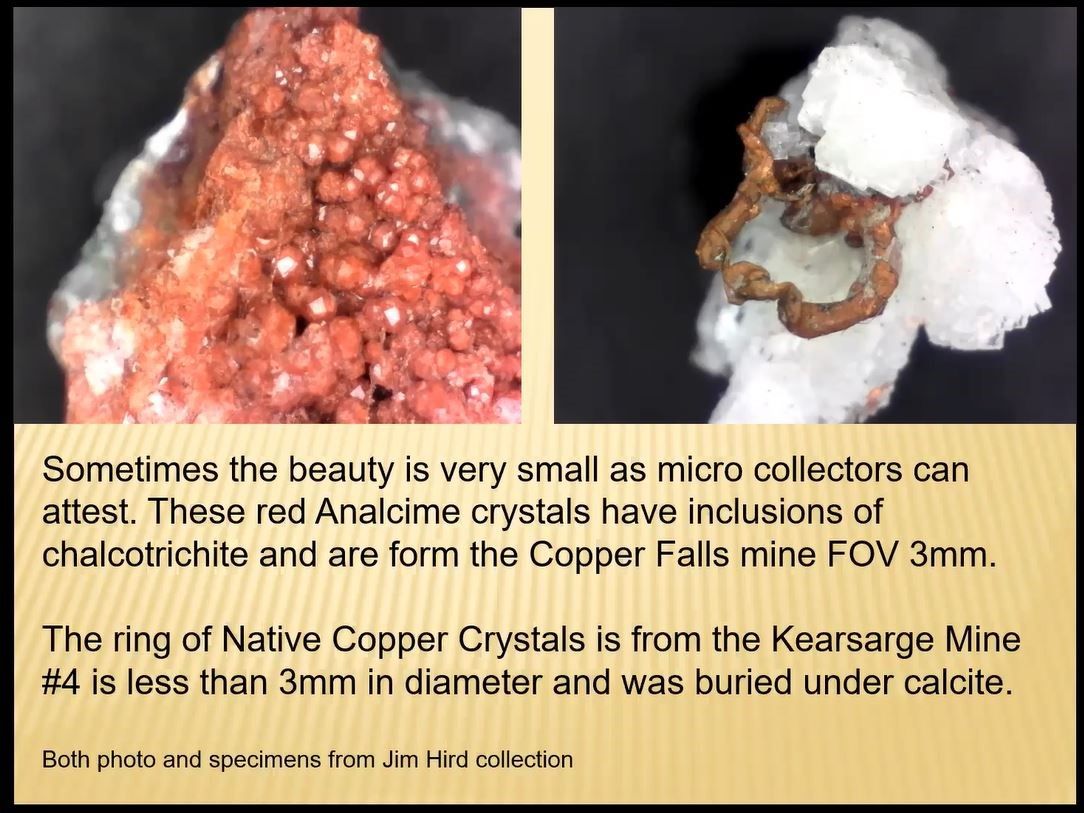

For collectors of microminerals, Jim showed the following two tiny specimens. The red mineral on the left contains chalcotrichite (copper oxide) and the brown ring-shaped mineral on the right is native copper embedded in white calcite.

With that final slide, Jim stepped off camera to gather some additional copper specimens for “show and tell” purposes. Before Jim could come back on screen, enthusiastic MSDC members jumped in and began sharing their own copper specimens.

When Jim returned with additional minerals and copper-related artifacts, a lively question and answer session ensued and blossomed. One question pertained to whether or not the copper deposits actually extended beneath Lake Superior, toward Isle Royale and beyond toward Canada. Jim responded in the affirmative and referenced the earlier slides with the concave multilayered deposits which extended north from the UP, across Lake Superior, to the Isle Royale and on toward Canada.

Another question was if miners or collectors ever found silver nuggets along with the copper deposits. Again, Jim responded in the affirmative. After multiple MSDC attendees also shared their favorite copper specimens, several folks expressed an interest in exchanging emails and trading, including NJ copper, for example, for UP copper.

Dave Hennessey, President of MSDC, thanked Jim for his extraordinary presentation on the copper mines of the U P. MSDC’s enthusiastic attendees seconded that gratitude with their applause. It was a marvelous mix of “then and now” perspectives on a very important part of copper mining history in the U.S.

For those who want further information, Jim Hird referenced the following booklet, Red Gold and Tarnished Silver: Mines and Minerals of the Lake Superior Copper District. It was produced by the Copper Country Rock & Mineral Club in 1998 (42 pages) and is available for $7 per copy.