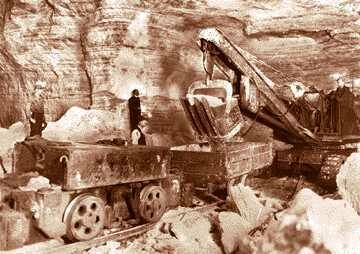

Underground Salt Mine in Detroit

Over a thousand feet beneath the Detroit streets is a subterranean metropolis few are allowed to enter.

Source: Atlas Obscura, Meg Neal. Article provided by Dan Teich, MSDC Director

Detroit is known for many things: the auto industry, hockey, and Motown. But there is another part of the city far fewer people seem to be aware of, and it lies directly underneath their feet.

Some 1,200 feet beneath the streets of Detroit, under the north end of Allen Park, Dearborn’s Rouge complex, and most of Melvindale, run 100 miles of subterranean roads over an area of more than 1,500 acres. It is the Detroit Salt Mine, and, as a Detroit industry, it is older than automobiles. As a geological entity, this salt deposit is older even than the dinosaurs.

Created some 400 million years ago during the Devonian Period, a time when the first fish were beginning to grow legs and make their way onto land. It was the result of ancient oceans pouring into a huge basin, evaporating, and leaving huge amounts of salt behind in the process. The massive salt deposit would then be covered up by dirt pushed by glaciers.

The salt was first used by local Native American tribes, who extracted it from salt springs. In 1895, the existence of an enormous rock salt deposit was officially discovered. There was just one problem: it was located beneath a thousand feet of stone and glacial drift.

Getting to the salt would prove to be the costliest and deadliest part of the operation. Six men were killed during the dig, and the Detroit Salt and Manufacturing Company was bankrupted in the process. The 1,060-foot shaft was finally completed in 1910. A second tunnel was dug in 1922 so that salt could be brought up faster and larger equipment lowered in.

Miners rode down to the mine smushed face to face in a tiny elevator. Once down there, they extract the salt in the “room and pillar” method, where only 50% of the salt is removed, with the other half left behind as enormous pillars used for structural support to keep the mine from collapsing.

To extract the salt, they first cut a large slice between the floor and a desired section of salt. Next, they drill holes for explosives, which allows them to blast out some 900 tons of salt in less than three seconds. The salt is then crushed, and thousands of feet of conveyor belt move the salt to the hoisting shaft, where it is lifted out in ten-ton loads. The mine itself is a relatively clean and spacious place to work, as far as mines go.

In a 1925 Detroit News article, miner Joel Payton told about his salt mine job. “The only dirty part of this job is going down to work,” Mr. Payton explained.

“I have to wear this old outfit because the big buckets that take us down get smudgy from the action of the sulphur water on the iron of the buckets.

“The mine itself is dry and clean as pure rock salt in a solid vein 35 feet thick is bound to be. The high vaulted rooms that we have hollowed out have sparkling white floors, walls and ceilings.”

Payton continued, “One reason we don’t have any rats in our Detroit mine is because the rats would have nothing to eat except the leavings of our lunch pails. And by the way, not only are there no rats or cockroaches or other living creature in our mine, but also no remains of living things from past ages. The salt vein is, of course, a dried up sea that once covered this section for hundreds of miles. You’d naturally suppose that some fish or vegetation would have been pickled or fossilized in the brine as it hardened. But I’ve never seen a single fossil or sea shell or any remains of that kind”

Today, the salt from this mine is used exclusively as road salt. Public tours are currently unavailable.